The Weekly Reflektion 51/2025

In an enlightened organisation openness is encouraged and mistakes are treated as sources of insight instead of shame. Individuals do not fear to report, in fact the only fear that should be respected is the fear of failing to learn from what is reported. Openness is a foundation of science and fosters a culture of learning and experience transfer that advances knowledge and helps to discards theories and hypothesis that are no longer valid. Secrecy may be convenient after an incident, however, it will most likely lead to further failures, and accidents that cause harm.

Three Mile Island

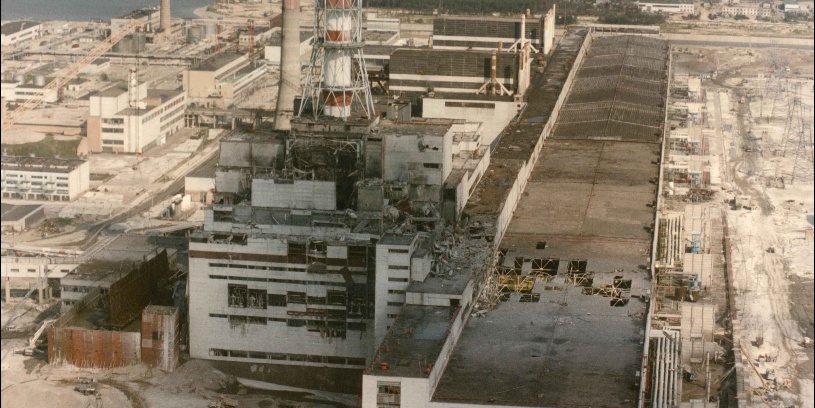

Chernobyl

Do you appreciate the value of openness for learning?

Effective learning, especially in situations involving complex systems, high risk, and public safety is difficult. When information is shared transparently, societies are better able to understand events, correct mistakes, and prevent future failures. The contrast between the public handling of information after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the United States and the Chernobyl disaster in the Soviet Union, illustrates how openness, or the lack of it, shapes learning outcomes at institutional, societal, and global levels.

After the Three Mile Island accident, 28th March 1979, communication was imperfect and at times confusing, but the overall response moved toward disclosure. The accident occurred at 4 a.m., was reported to the Pennsylvania Emergency Agency at 07:02 a.m., first reported by a local Harrisburg radio station at 08:25 a.m. and by 10 a.m. a press conference was scheduled. Investigations were made public, technical failures were documented, and independent bodies analyzed what went wrong. Media coverage, congressional hearings, and regulatory reviews exposed weaknesses in reactor design, operator training, and emergency communication. This openness enabled learning: nuclear safety standards were strengthened, operator training programs were redesigned, control-room ergonomics were improved, and regulatory oversight became more rigorous. Crucially, the accident became a shared case study from which engineers, policymakers, and educators worldwide could learn.

The contrast with Chernobyl is striking. In the immediate aftermath of the explosion on 26 April 1986, Soviet authorities suppressed information, delayed evacuations, and minimized the scale of the disaster. The delayed evacuation exposed many thousands to radiation. The lack of transparency prevented timely public protection and obstructed early scientific understanding of the event. Even within the Soviet system, engineers and officials were denied full access to accurate data on the causes of the failures. This secrecy severely limited learning from the disaster, for example, the design flaws in the RBMK reactor and systemic cultural problems, including fear of reporting errors. These problems remained unaddressed for years. Only after political changes and international pressure did fuller information emerge, by which time the human and environmental costs had multiplied.

The learning implications of this contrast are profound. Openness accelerates feedback loops: errors are identified sooner, assumptions are challenged, and improvements are made based on evidence rather than ideology or reputation management. Secrecy, by contrast, freezes learning. It protects institutions in the short term but amplifies damage in the long run by allowing flawed systems and behaviors to persist.

‘Openness’ is often one of the values that management promotes in their speeches, and companies display in the posters that decorate the office walls. Living up to the expectations of openness requires an openness that sometimes exceeds what the management are prepared to commit to. Resolving this dilemma is a key factor in becoming an enlightened organisation.